Signed into law on August 16, 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is the most significant long-term commitment made by the U.S. government to encourage and support a clean energy future. The IRA works through the Internal Revenue Code (Code) in ways that fundamentally change the landscape on how clean energy tax credits and incentives are designed, awarded, and monetized.

The regulation, taxation, and financing of energy projects has been an integral aspect of my law practice for decades. These are exciting times now, as the structuring of energy tax credits under the IRA expands on a number of themes that I first covered in an energy and environmental project finance book I coauthored for Oxford University Press back in 2010. Then, as now, my perspective is shaped by my work for clients in the traditional and emerging clean energy sectors.

Why launch a series now about the energy tax credits that were extended, modified, or introduced by the IRA?

- Many of the IRA energy credits run until 2032, so project developers still have ample opportunity to get their projects underway while credits remain available.

- The Treasury and the IRS have yet to provide us with many important details on IRA implementation, with much of the guidance having been provided in Notices and proposed Treasury Regulations. But while the details are being ironed out, taxpayers still need to move forward with their projects, and tax returns need preparation. As project owners and funders continue to seek assistance, it remains critical to remain vigilant and stay on top of the large number of new developments.

- Two important technology-specific credits expire at the end of 2024. They will be replaced in 2025 by two technology-neutral credits. The technology-neutral credits do not expire until 2032, or until certain greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) are reduced to specific levels set out in the Code (most likely, later).

- Projects that seek to qualify for IRA energy tax credits and which begin construction in and after 2025 will need to meet statutory requirements not required for earlier projects.

Developers and investors would be well advised to consider the tax consequences to their energy projects during the second half of 2024, which I look at as a transition period.

In this Q&A with Andie, Energy Tax Credits For A New World, I aim to provide an overview of the IRA as it relates to many important energy credits. I will take deep dives into some of the requirements and mechanics of some of these credits, and I will look at the ways in which these credits can be monetized.

Through Summer and Fall 2024, Readers can look forward to reading this extended occasional series presented in the following parts:

Part I: Overview of Energy Tax Credits under the IRA

Part II: Production Tax Credits and Investment Tax Credits: The Old and The New

Part III: Overview of Bonus Credits

Part IV: Prevailing Wage and Apprenticeship Bonus Credits

Part V: Domestic Content Bonus Credits

Part VI: Energy Community Bonus Credits

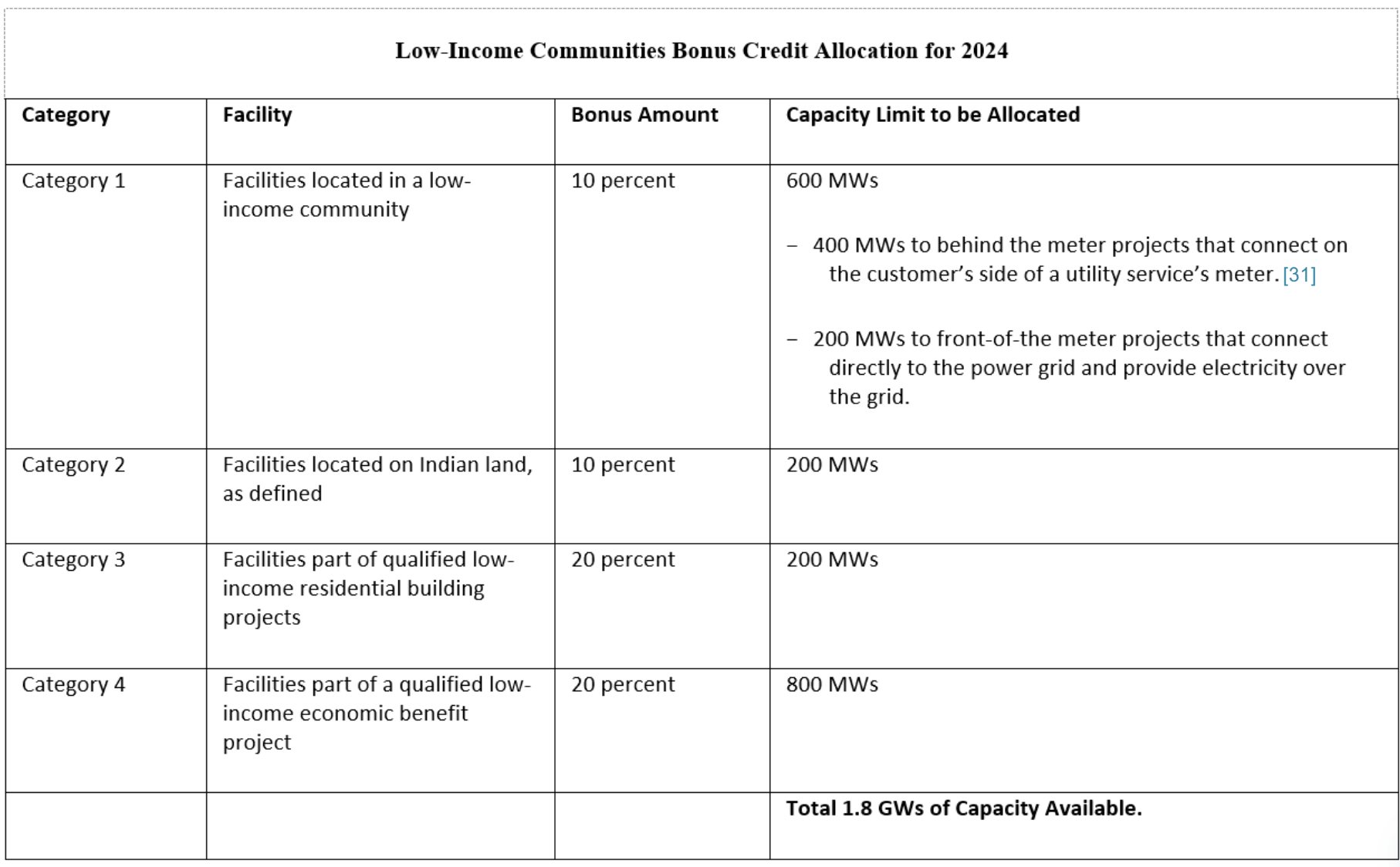

Part VII: Low-Income Communities Bonus Credits

Part VIII: Monetizing Energy Tax Credits

Part XI: Changes to Traditional Tax Equity Financing

The IRA’s tax benefits are enormous. As a result, when a “qualifying energy project” is properly structured and timed, it can receive tax credits that reduce certain related costs by more than 50 percent.

As I launch this series, I would like to extend my gratitude to Nicholas C. Mowbray for his comments and exceptional assistance.

Part I: Overview of Energy Tax Credits under the IRA

“Dozens of countries are widening the gap between their economic growth and their greenhouse gas emissions. . . . If these trends continue, global emissions may actually start to decline,” observed Umair Irfan writing for Vox.[1]

What is the importance of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) to energy tax credits?

The IRA has strengthened the United States’ long-term commitment toward a clean energy economy. It is the most ambitious U.S. effort to date to incentivize the development of renewable energy technologies[2] that can help to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The IRA targets the enormous capital expenditures needed to create, commercialize, and broadly make available renewable energy technologies. The IRA’s goal is to lay out a path toward a net-zero GHG economy by 2050.[3]

How does the IRA affect energy project funding?

The IRA has brought about major changes in the ways in which energy projects are structured and funded. It provides for loans, grants, financial and technical assistance, rebates, and energy tax credits. About $400 billion has been allocated for clean energy innovation, technology, and manufacturing. Of this funding, about $260 billion applies to the extension and modification of existing tax credits and the introduction of new ones. In fact, more than 70 percent of the IRA’s benefits are delivered through tax incentives. Now, more than 20 tax credits allow for monetization that supports clean energy generation, develops related manufacturing capacity, incentivizes the increased use of clean vehicles and energy sources, and increases carbon capture programs.[4]

How does the IRA target GHG emission?

The IRA uses funding and financial incentives to support research, development, and commercialization of low- and zero-GHG emission technologies. It also seeks to steer project developers to locate their projects in “energy communities” or “low-income communities”; to pay prevailing wages and encourage the training of registered apprentices; and to increase the use of domestic content components in project-related manufacturing and construction processes.

Have the IRA initiatives been effective?

Initial IRA success stories are very positive, but we have a long way to go. In 2023, “more solar panels were installed in China […] than the US has installed in its entire history. More electric vehicles were sold worldwide than ever.”[5] As the United States seeks to become a global leader in decarbonization and to compete with other major economies like China, the IRA is creating “new opportunities for workers […] and lower costs for America’s families.”[6]

Congress also seeks to ensure that monies provided by the IRA strengthen domestic supply chains and ensure the nation’s energy security in its transportation modes. The IRA is boosting domestic manufacturing for critical renewable energy components, while partially funding the construction of renewable energy projects through its rigorous domestic sourcing requirements.

In 2023 the American Council on Renewable Energy found that, “One of the most notable impacts of the IRA is how quickly it helped to onshore new advanced green manufacturing. More than 83 new or expanded wind, solar, and battery manufacturing facilities have been announced since August 2022, including 52 plants for solar production, 17 for utility-scale wind production, and 14 for production of utility-scale battery storage.”[7]

Notwithstanding some initial successes, two years after passage of the IRA, there are some serious concerns that some of the credits are unworkable, and that the IRA’s domestic sourcing requirements have fallen short of expectations.[8]

Is it possible that the IRA could be dismantled by future Administrations?

Yes. It is possible. Perhaps, a better question might be should the IRA be dismantled? Is it in our best interests to shut down the onward innovation of a thriving high-growth, high-benefit fledgling U.S. industry segment, substantially underwritten by the government, and made available to the residents of a leading market economy?

What makes the IRA different from prior environmental and climate efforts?

The IRA is fundamentally different from the carrot-and-stick approaches of many prior U.S. environmental and climate laws. It has an incentives-based focus: it does not rely on traditional regulation and enforcement to achieve its desired outcomes. It proactively seeks to encourage long-term commercial investments to decarbonize transportation, manufacturing, and construction. The IRA is popular among early adopters. Kimberly Clausing, the Eric M. Zolt Chair in Tax Law and Policy at the UCLA School of Law, noted in a 2023 interview, “There’s a lot of things to like about these tax credits […] they’re broad, they’re longer lived than prior tax credits, and they don’t phase out as quickly. They’re more flexible than prior tax credits. They’re more transferable and refundable, and that enables them to be ultimately more effective.”[9]

The IRA’s long-term focus on tax credits, financial incentives, and monetization may offer prospective project developers a degree of certainty in their planning; persuade investors to commit to clean energy undertakings; and broaden the pool of capital available to do so. So far, the facts speak for themselves: in the first year after the IRA’s enactment, 280 clean energy projects were announced across 44 states, representing $282 billion of investment.[10]

What deference will be given to Treasury Regulations addressing the IRA provisions?

Since passage of the IRA, the Treasury and the IRS have been carefully moving through the details of its rollout.[11] At the date of this writing, many critical questions remain unanswered. In addition, for many decades, the Treasury and the IRS have enjoyed broad latitude on the administration of the laws. But the legal landscape might be changing. On June 28, 2024, in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, the U.S. Supreme Court effectively overturned the so-called Chevron doctrine. Chevron is a 40-year-old Supreme Court case that afforded federal agencies a degree of deference in the reasonable interpretation of a statute that fell within their areas of expertise.[12] As a result, many questions will be raised about many laws, along with the frameworks for their roll out and enforcement. Although the Treasury and the IRS will be able to claim broad expertise in some areas of the tax law, it is likely that there will be disputes and litigation over the deference to be given to climate-related tax regulations.[13]

What is the starting point for the IRA’s focus on tax credits?

Let’s take a walk down memory lane. Federal income tax credits for wind and solar energy were first enacted in The Energy Tax Act of 1978.[14] They were structured as refundable 10 percent tax credits for energy property and equipment that produced electricity using wind and solar sources. Later, The Windfall Profit Tax Act of 1980 extended the expiration through 1985, increased the credit to 15 percent, and removed a taxpayer’s ability to get a tax refund based on the value of the credit.[15] The Tax Reform Act of 1986 reduced solar energy credits from 15 percent to 10 percent and extended them through December 31, 1988. Further energy credit extensions for solar property were enacted between 1988 and 1991.

With The Energy Policy Act of 1992,[16] Congress made solar energy credits “permanent” and named them “investment tax credits” (ITCs). The same legislation also enacted the “renewable electricity production tax credit,” or the PTC. When the PTC expired in 1999, it was subsequently extended and expanded to include additional energy technologies.

The Energy Policy Act of 2005 increased the ITC for solar energy from 10 percent to 30 percent, and it extended the credit to additional types of energy property.[17] It did not, however, extend the PTC for solar and refined coal facilities. This meant that from 2005 until enactment of the IRA, the PTC was not available for electricity that was produced from solar energy.

Does the IRA move away from technology-specific tax credits?

Yes. Before the IRA, the PTC at Section 45 and the ITC at Section 48 were the two principal energy tax credits. They were enacted to encourage the development of U.S. wind farms and solar arrays. Both the PTC and the ITC included technology-specific statutory provisions that had been amended over the years to include additional technologies identified by Congress.

The IRA modified and extended both the Section 45 PTC and the Section 48 ITC through the end of 2024 at which point they will be replaced by the next generation of technology-neutral credits: the Section 45Y Clean Electricity Production Tax Credits (CEPTC) and the Section 48E Clean Electricity ITC (CEITC).[18] The rest of the energy tax credits that the IRA modified or introduced took effect for projects beginning on or after January 1, 2023, with most of those credits expiring on December 31, 2032.

In the next part of this series, we will take a look at the production tax credit (PTC), the investment tax credit (ITC), and their progeny. Many of the IRA tax credits are modifications or expansions of the PTC and the ITC. It is an important next step to consider the underlying framework of the old credits and the new.